Could Europe’s ambitious open science cloud (EOSC) change the face of research?

July 10, 2023

By Linda Willems

Open science expert and campaigner Gareth O’Neill believes it can. Here, he offers a fascinating insight into its future potential.

Gareth O’Neill’s first attempt to make a dataset “FAIR” is etched in his memory. “I was working as a theoretical linguist researcher and had no clue what the term even meant. Looking back, I wish I had found out first — it turned out to be a lot of work!”

FAIR opens in new tab/window data complies with a set of principles designed to make research data easy to find and reuse. Luckily, Gareth’s first experience with FAIR didn’t deter him. Instead, it sparked an appetite for sharing and managing research data and led him to new role: he is now Principal Consultant on Open Science at Technopolis Group opens in new tab/window. His impressive CV also includes an Ambassador position for Plan S opens in new tab/windowat cOAlition S opens in new tab/window, the initiative seeking to make all publicly-funded scientific publications open access. And he leads an EU-funded group opens in new tab/window exploring the development of indicators and metrics for open science.

Gareth O’Neill

Drawing on the power of FAIR

Importantly, Gareth also heads up a team looking at policy and strategy for the European Open Science Cloud (EOSC) opens in new tab/window. Announced with great fanfare by the European Commission in 2015, EOSC is currently under construction, with in-kind and financial contributions expected to top €1 billion in the coming seven years. Its aspirational vision is to provide European researchers, innovators, companies and citizens with “a federated and open multi-disciplinary environment” where they can publish, find and reuse data, tools and services.

Gareth explains: “It is essentially a virtual space for researchers to share or find digital objects and to collaborate, both within their disciplines and across their disciplines. Then on top of that come the different services offered by public infrastructures and commercial service providers, which researchers can use to visualize, process and exploit the data they find.”

He adds: “It is a vital tool for supporting open science at a European level, and what we are seeing is that many public research infrastructures are starting to link up to it.”

Crucially, EOSC’s ultimate goal is to develop a “web of FAIR data and services” for science in Europe. According to Gareth: “EOSC is not a box where we store everything, it is the connection between the different data repositories, datasets and services that are out there. And that connection is made through the common language of the FAIR principles, so, it’s important that all datasets in EOSC are FAIR, even if they aren’t necessarily or at first open.”

Accelerating the pace of discovery

For Gareth and others working on the project, one of the most powerful aspects of EOSC is the opportunities it offers to mine and leverage the oceans of data we generate.

“Humans cannot deal with the amount of data that we are now producing, not just within a discipline but also across disciplines — it’s almost doubling on an annual basis,” he explains. “So the idea here is to have a federated set of data: I’m talking billions and later potentially trillions of datasets that are machine actionable. Clever algorithms, machine learning and eventually maybe artificial intelligence can start combining research data to a degree never seen before, we assume exponentially.”

According to Gareth, that opens the door to “correlations that we never would have dreamed of, ultimately providing us with potential new avenues of research and breakthrough discoveries.” He adds: “It’s important to note that humans are not irrelevant in this process: the machines will just basically point us in certain directions. It will still be up to us to do the research.”

How it might work in practice — a case study

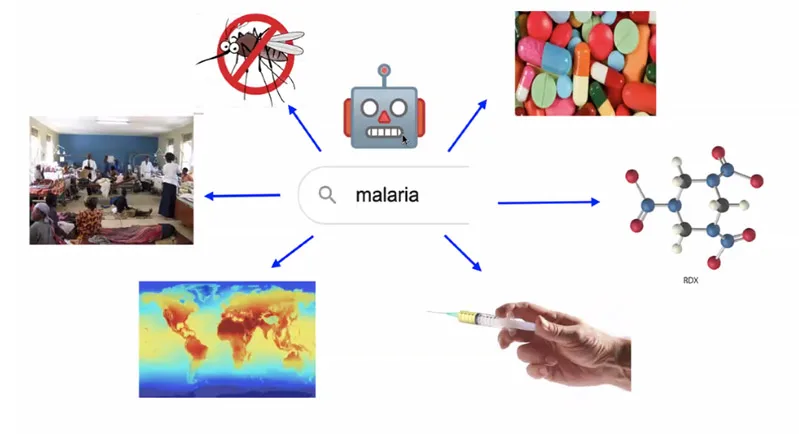

A visualization of how EOSC might respond to a query on malaria. (Source: Gareth O’Neill)

Gareth says: “I imagine in the future a simple search engine where I type in a keyword such as ‘malaria’ and the machines go to work on a federated dataset — linked up through EOSC — containing billions of datasets. It will quickly pull out from the publications that malaria is associated with mosquitos with, let’s say, 95% percent accuracy — 5 percent would be random noise we can ignore. The machine will then start identifying links to malaria, links to mosquitos. For example, looking on the left in my visualization, it will look to see where malaria outbreaks have taken place and at what time of the year.

“It will then start mapping the information it’s gathered to historical data from the EU’s Copernicus satellite, looking to see what the temperature, humidity, air pressure and water level was in those areas, looking for factors that correlate with those malaria outbreaks and identifying times when they didn’t occur.

“At the top of the visualization, we see it looking through commercial data on particular medicines to see what was on sale during the outbreaks and what was selling well. It can then start digging into the chemical databases of those medicines and chemicals, looking for the active components, what seems to work, what doesn’t, and potentially start providing lists of future medicines, future vaccines, and so on. It will have done all this in a matter of seconds. Given the volume of datasets here, the same process would probably take a human, or even thousands of humans, years if not decades!”

Preempting future pitfalls

For Gareth and others working in the field, while creating the federated dataset brings many advantages, there are also potential issues that need to be dealt with. “When you have such an enormous dataset and you start running learning algorithms on it to develop AI, what could it potentially become in the future? How clever will it get? That’s something we need to think about. And there are other issues: we did not know, for instance, that when Facebook was taking our data, it would be used very quickly to actually change human behavior and to influence politics, political procedures and votes.”

He adds: “Another aspect is looking at who can use this data that’s open. Potentially, someone could just hoover it up and do something with it. In many cases, data on dual-use technology (technology that can be used for both civilian and military applications) is not published publicly, but we don’t know if minor components of particular systems of developments could be potentially recombined or combined by a really intelligent AI system in the future to create weapon systems for use against us. Safeguards may be required to watch for this and control it.”

Another element necessary for EOSC’s success is widespread adoption of the FAIR principles by Europe’s member states. To date, uptake is sporadic but growing.

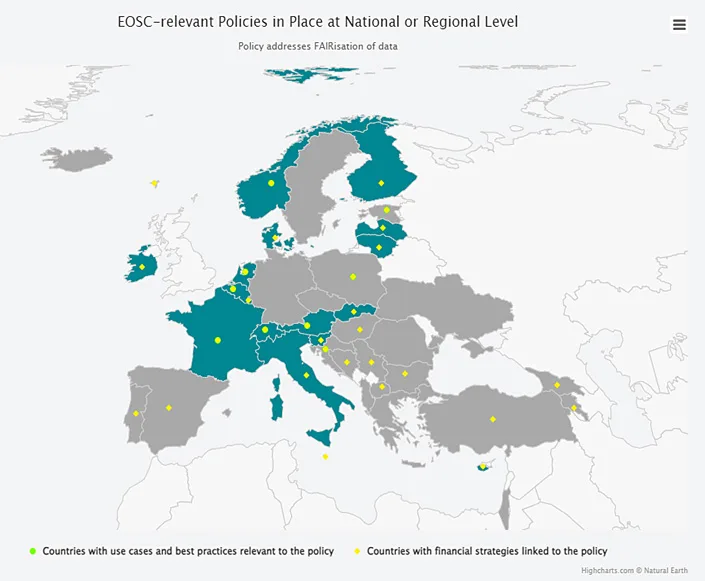

EU member states and associated countries with EOSC-relevant FAIR policies are in dark green. Green dots indicate countries with use cases and best practices; yellow dots indicate countries with related financial strategies. (Source: The EOSC Observatory opens in new tab/window)

Gareth explains: “FAIR is quite complicated to implement at a national and institutional level, and I think it will take time for that to come. But what we definitely see from member states and associated countries is interest and initiative to do this and they are now starting to assign national budgets to drive the support of FAIR data.”

He points to a few prominent examples: “France, for instance, is now providing institutions and researchers with training and support for FAIR data at a national level, while Greece has set up a data management expert guide to support researchers in the social sciences. Poland is providing templates for data management plans across the disciplines, specifically for researchers that are funded under their funding programs, and Switzerland is developing digital tools to help researchers make their data FAIR.”

He concludes: “While there are major breakthroughs coming if we can achieve our vision for EOSC, we will need to keep in mind potential issues that may arise from opening up such an enormous dataset, and from new discoveries that we are not able to control or foresee.”

FAIR data, open data: What do the terms mean?

FAIR data are data that comply with the FAIR Principles opens in new tab/window, a set of guidelines designed to make digital assets Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable. An important element of making a data record FAIR is providing rich and accurate metadata — in other words, data that describes the record, including a unique identifier, who created it, what the record contains and any rules governing its use. As Gareth explains: “The FAIR principles are in essence a common language for machines to communicate with each other about data, and if the machines can talk about the data then we can find it, we can know what it contains, we can access it, we can interoperate it and we can reuse it.”

According to the Open Knowledge Foundation opens in new tab/window, data records are considered open when anyone can freely access, use, modify and share them for any purpose, “subject, at most, to requirements that preserve provenance and openness.”

As Gareth points out, FAIR data are not necessarily open data and vice versa. “The terms are often confused, but, critically, they are very different. For example, a dataset may be open, but if there is no metadata attached, it’s not FAIR; in fact, it’s useless because a machine cannot find it to index it. Or a dataset might be in a format that’s completely unbeneficial to the researcher.”

He adds: “Equally, some data can never be open: for example, biomedical, military and intelligence data. Other data may be embargoed for commercialization reasons.”

Contributor

LW