Research impact assessment: a mandate for change

February 16, 2024

By M’hamed el Aisati

Image from the cover of Elsevier's 2023 report Back to Earth: Landing real-world impact in research evaluation

A new survey of the research community shows strong support for assessing research by its real-world impact

Most developed countries spend between 2% to 3% of their annual gross domestic product on research and development — an investment fueled by the argument that public money spent on research brings public benefits. But as any good researcher knows, assumptions should be backed up with evidence.

The argument for research spending is clear enough: It improves our health, our technology and our quality of life and generally makes the country and the wider world a better place. Indeed, meeting society’s challenges is one of the most common motivations for researchers to do research in the first place.

For the most part, policymakers have been content to let researchers get on with their work, assuming that a positive impact will follow. However, several studies have shown that a substantial portion of research funding is routinely “wasted” on poorly designed and redundant studies.

Proving the value of research

Against this background, it is therefore increasingly vital to show evidence for the societal impact of research, especially when financial times are harder, as they are today. Everyone in the world of research — government officials, funding agencies, research institutions, even researchers themselves — is under pressure to show why research matters.

That was evident when Elsevier surveyed researchers, academic leaders and funders for its report Back to Earth: Landing real-world impact in research evaluation, published in November 2023. Of the 400 respondents, just 1% were opposed to using real-world impact on research evaluation, while 64% said the current system of research evaluation prioritizes academic output above real-world impact.

The dialogue may not be as smooth as many researchers hope. In the UK, a survey earlier in 2023 by the Campaign for Science and Engineering opens in new tab/window presented some stark results. A majority of the UK public supported a savage 50% cut to the government R&D budget if the money went instead to nurses (most of whom work for the government-funded healthcare service and who are perceived as underpaid) or to lowering energy bills. Almost half of respondents said they would only invest more in R&D when the economy is in better shape. And more than a third could think of no, or very few, ways that public investment in R&D improves their lives.

Science and the culture wars

And it’s not just the UK. Public support for science appears to be waning in many places. This is despite our global transition to a science-based society and the triumph of science during the pandemic, with innovative vaccines deployed in record time. Yet the public image of science is declining, in part, perhaps, because scientists have been caught up in the culture wars and identity politics.

That seems to be the case in the United States. “Between November 2020 and the end of 2021 is when you see the steep decline in trust,” says Dr Brian Kennedy opens in new tab/window, a Senior Researcher at the Pew Research Center, where he focuses on science and society research. “That’s when the share of Americans who say they have a great deal of trust (in scientists) goes down by 10 (percentage) points.”

In response to such fears, many in the research community have been keen to rely on quality assurance: peer review of articles and grant proposals, internal assessments, and bibliometrics such as citations to high-profile studies. The strategy has been to demonstrate that the work being paid for is of the highest quality.

That’s done partly because it tells a reassuring story, but also because demonstrating impact in society is hard to assess. But there is a growing consensus that the research community needs to come together to find a way to measure and report impact — and fast.

A latent impetus for change

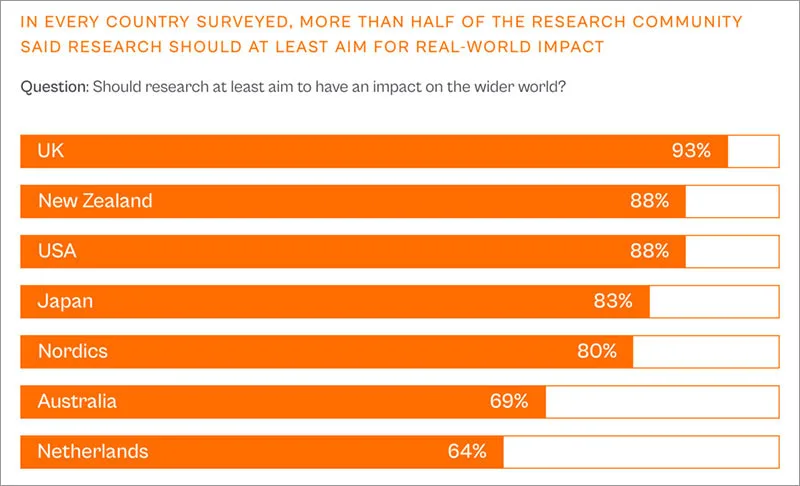

Elsevier’s Back to Earth report makes clear the strength of opinion. Based on a survey of 400 members of the research community from seven countries, it highlights community attitudes towards the current situation and what could be done to improve things.

It shows that almost a fifth of the respondents argue that the current system of research impact assessment is ineffective. Asked whether the current system incentivizes real-world research — in other words, whether it’s doing a good job — 28% of respondents said it’s not effective.

About 18% describe current assessment systems as crude, 15% think they are outdated, 20% opaque, and 13% discriminatory. In contrast, just 39% would describe them as sophisticated, 42% futureproof, and 46% transparent.

Source: Elsevier, Back to Earth (November 2023)

The results echo those from Elsevier’s separate listening exercise in the summer of 2023, where four roundtable conversations brought in the views of 40 academic leaders and heads of funding bodies from 18 countries. Those discussions also identified a strong appetite for change. Participants agreed that the current research assessment system, with its emphasis on articles and citations, does not align with desired outcomes. There was broad support for reform toward a system that also addresses education and societal impact.

If the results of the exercise and the survey hold across the wider academic system, that could indicate the signs of a real problem, both for those being assessed and for those doing the assessing. At the very least, they show that a significant number of people in the academic and research community believe there is room for improvement. Combined with changing sociopolitical factors, this surely makes moves towards real-world impact-based research evaluation an urgent imperative.

Download the report

Elsevier’s Back to Earth project surveyed 400 researchers, academic leaders and funders worldwide on the way ahead for research impact assessment. To discover what they said, download the report.

Contributor

MEA