Temple Grandin on the kinds of minds science desperately needs

Fort Collins, Colorado | March 31, 2017 | 12 min read

By Alison Bert, DMA

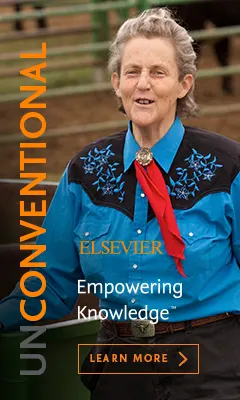

Dr Temple Grandin, Professor of Animal Sciences at Colorado State University, poses in her livestock handling system after teaching a class at the university. (Photo by Alison Bert)

Renowned animal scientist and autism advocate talks about “turning on young students” to science — and not just the obvious candidates

On the opening day of her livestock handling class at Colorado State University, Prof. Temple Grandin opens the gates of the steel maze that would guide the cattle, in single file, to a squeeze chute for examination. Used by livestock facilities around the world, her system is designed to keep the animals calm and prevent accidents.

As the students gather around, Dr. Grandin asks her first question:

“Has anyone here never touched a cow?”

Prof. Temple Grandin teaches her livestock handling class at Colorado State University. (Photo by Alison Bert)

The question, while basic, reveals much about the world of Dr. Grandin. Her reality is based on observation: insight gained from stroking the coarse hair of a cow, noticing how the cows turn to watch a front-end loader picking up hay across the field – seeing the world “in pictures,” literally. Mention “cow,” she says, and photorealistic pictures of all kinds of cows flash through her head “like Google Images.” It’s an ability she’s had since childhood, when she struggled with autism so severe she would have been institutionalized were it not for her mother finding an alternative path to education – with teachers that recognized Temple’s special needs and talents, and a mind that would turn out to have the capacity of genius.

Since then, autism has continued to define her existence, but in a way that has led to uncanny insights into the minds of animals. Her ability to see in pictures and sense the things that spook them – a waving flag, for example, or a reflection in a puddle – has led her to create more humane livestock handling systems. And more recently, autism has enabled her to better understand the minds of people and how their thinking styles relate to their scientific abilities. It’s an understanding that has led to a new calling – as role model and mentor for school children – which she pursues as fervently as her livestock business and long-time autism advocacy.

A day earlier, she drove three hours each way to a school in Pueblo, Colorado, to spend time with fifth-graders. She talks with passion about meeting with young people, especially those who might have trouble finding their strengths and the career paths they can lead to.

“Different people bring different strengths”

“I’m interested in turning on young students,” she says. “I want to get kids back to doing hands on things. We’re got kids today who don’t know how to use scissors and a hammer.” But beyond that, she wants to see them find their place in the world of science.

“Different people bring in different strengths,” she says. “For me to try to be a computer programmer is pretty stupid; that’s not going to work.” Computer science is too abstract for her, she explains, but as a visual thinker, she brings something just as important to science:

When I look at the methods of an experiment, I see the actual animals, I see the experiment. So when I review journal articles, I tend to really go over the methods: the sampling procedures, what kind of animals they use. Other people are tearing apart the statistics, and I’ll (notice) they didn’t even tell me what breed of pig they used in the experiment. And that can affect the results in a really bad way.

She goes on to recite the various breeds of pigs, cutting the list short to emphasize her point: It all comes down the observation and attention to details, she says, and some people are naturally better at this than others. She calls these people “visual thinkers” – the kind of students who, as children, are usually good at art and building things. And they’re in good company in the world of science, she says, mentioning Thomas Edison, Nikola Tesla and Jane Goodall. They tend to be good at designing experiments and intricate lab equipment – and science desperately needs them, she says. But unfortunately, they’re not making it in the science curriculum.

“They’re getting screened out with all the rigid math requirements,” she says, mentioning the challenge posed by abstract mathematics like algebra.

“We need the visual thinkers,” she proclaims, speaking in the same strong voice at the dinner table as in her classroom. “We need them to prevent accidents like Fukushima. … They put the emergency cooling pump and its generators in a non-waterproof basement. The abstract mathematician mind doesn’t see the water seeping into the basement and flooding all the electrical equipment. I’m not talking nuclear science here; I’m talking, electrical stuff doesn’t run underwater – period.”

Dr. Grandin punctuates her speech to emphasize her points, much like she pokes the icons on her iPhone harder than necessary to take a call or reply to an email. She is fond of the iPhone and uses its simple interface to show the value of visual thinking in the scientific process.

“It was made by an artist, not by an engineer,” she says. “Steve Jobs was an artist. But an engineer had to make it work.”

Collaborating with different kinds of thinkers is crucial for people in science, she says. “They need to recognize each other strengths, and they need to work together.”

Dr. Temple Grandin talks shop with her research and business partner Mark Deesing after they teach a class together at Colorado State University. (Photo by Alison Bert)

An unlikely collaborator

In her own career, she has spent nearly a quarter century collaborating with a man from a very different background than her own. Mark Deesing couldn’t afford to go to college, so he made his living doing what he knew: training horses and fitting them for shoes. But his lack of formal education came back to haunt him when he came up with a unique theory about animal behavior – that the position of the hair whorl on a horse’s head is related to temperament – but couldn’t get anyone to take it seriously in the scientific community. Except for Dr. Grandin.

Deesing impressed Dr. Grandin with his keen observation skills and his desire to do scientific research. She taught him how, and the two have since published their research in journals and a book published by Elsevier in 2013: Genetics and the Behavior of Domestic Animals. Now Deesing travels around the world building livestock handling facilities that are better for the animals and the businesses alike.

Mark Deesing teaches students the importance of precise measurement in design and engineering as part of Prof. Temple Grandin’s livestock handling class at Colorado State University. (Photo by Alison Bert)

On this day, he assists Dr. Grandin with her class, teaching students the intricacies of design and engineering, where a few inches can mean the difference between getting 1,000-pound cattle to walk in single file or causing them to get stuck in a chute that’s too narrow. His lesson starts with a simple ruler as he explains the concept of drawing to scale and making sure the scale is small enough so that everything fits on the page. He motions to the livestock system he designed and says: “Look how big this is. If I would have drawn it as big as one inch equals 10 feet, the paper would have been as big as the room here.”

Despite sharing Grandin’s visual acuity and penchant for detail, Deesing is a world apart from her when it comes to daily life: he’s not autistic. Yet he credits her with teaching him about much more than how to be a scientist. “Even though she’s autistic,” he says, “she’s such a moral and ethical person. She understands the rules of being human, the rules of ethical behavior, the rules of morality. So she’s taught me to be a more ethical person. And she’s always reminding me what’s right and how to proceed with people and situations.”

For example, in his work designing livestock systems, occasionally owners or contractors are difficult or unwilling to follow his guidance. On one instance, he recalls, he got emotional and felt like quitting. But that changed when he called Temple:

She just said, ‘If you quit, the only thing that’s going to suffer is the animals.’ And that kind of brought me down to earth. By saying that one simple thing, she erased all that negative thinking I had and reminded me that my purpose was to better the life of the animal. My client was the cattle, and I’ve got to say the right thing and do the right thing for the cattle.

As an autistic person, she lacks “theory of mind,” Deesing explains, meaning it’s difficult or impossible for her to intuit why people think and act the way they do. But that’s hard to imagine when watching her interact with her students. She stays after class to talk with them about their work, and she answers their emails before any other business. Granted, there’s no small talk here. “She’s all business,” Deesing says. “She always see the goal line – the touchdown for these students, and she gets into a single-minded determination to see that every question is answered and every detail is covered. More than anything, I think she’s trying to shape them to her way of thinking. She’s very generous to share everything she knows so they have a full understanding of what they’re working on.”

“It’s like being taught by a superhero”

Prof. Temple Grandin holds the first day of her livestock handling class in the field. (Photo by Alison Bert)

In this class, many of the students are animal science majors, and others are taking the class as an elective. But most were drawn to the course because of the professor, having seen the movie about her life opens in new tab/window or read one of her books opens in new tab/window.

“I was just bragging to a neighbor – it’s like being taught by a superhero,” says Amber Elliott, an animal and equine science major from Reno, Nevada. “She understands animal behavior so well, and she’s trying to make a difference all over the place to make everything more humane.”

Prof. Grandin’s passion for animal welfare is what inspires Elliott’s classmate Taylor Bates: “She’s always talking about it. She gets very vocal, very loud, you can tell she’s passionate about it, which I think is really needed in this industry. I know there are a lot of people who worry about where meat is coming from and how the animals are treated. I like meat, but I’ve always been an animal lover. And I know vegetarians who are cool with Temple Grandin.”

A new chapter

But people rather than animals have become the focus of Dr. Grandin’s passion lately. At 69, she is embarking on a new chapter in her life – guiding even younger students to find their calling.

I want to see young people – especially those that may have had a few problems – be everything they can be. You know the geeky kid that comes up to me at an autism meeting? If he could be an honors student at CSU Engineering, I’d like to see him there. If it’s the art kid like me, I want to see him out there designing farm implements or something, or working for the power company. They need all these kinds of people. You need the engineer for certain kinds of mathematical things, but then you’ve got to have the millwright guys who can actually fix the stuff.

In science, she says, “you need all kinds of minds.”

Diversity of mind at Elsevier

Unconventional thinkers bring new perspectives to research and science, seeing key elements that are often overlooked. That’s why we support diversity of mind at Elsevier, employing people with different thinking styles to develop our tools and technologies – and to enable people of diverse abilities to access our research. By championing the unconventional, we empower people to go beyond the obvious, inspiring new opportunities for science and society.

Temple Grandin on autism

Dr. Temple Grandin has written numerous articles for scientific journals and books, many of them published by Elsevier. Here is a sample of her writings on autism.

Elsevier has made the following book chapter freely available until July 28, 2017:

Grandin et al: “The Roles of Animals for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder opens in new tab/window,” Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy, 4thEdition (2015)

This is her commentary for the journal Biological Psychiatry:

Grandin, Temple: “Visual Abilities and Sensory Differences in a Person with Autism opens in new tab/window,” Commentary, Biological Psychiatry (January 2009)

Temple Grandin on animal science

Here are some of Dr. Grandin's recent articles in Elsevier's journals. Those that are not open access are freely available until July 2, 2017:

Brittany P. Davis, Terry E. Engle, Jason I. Ransom, Temple Grandin: Preliminary evaluation on the effectiveness of varying doses of supplemental tryptophan as a calmative in horses opens in new tab/window, Applied Animal Behaviour Science (March 2017) – Open Access

Temple Grandin: Evaluation of the welfare of cattle housed in outdoor feedlot pens opens in new tab/window,Veterinary and Animal Science (December 2016) – Open Access

Grandin,Temple: Animal welfare and society concerns finding the missing link, Research article opens in new tab/window, Meat Science(November 2014) – Open Access

Camille King, Thomas J. Smith, Temple Grandin, Peter Borchelt, Anxiety and impulsivity: Factors associated with premature graying in young dogs opens in new tab/window, Applied Animal Behaviour Science (December 2016)

Chelsey Shivleya, Temple Grandin, Mark Deesing: Behavioral Laterality and Facial Hair Whorls in Horses opens in new tab/window, Journal of Equine Veterinary Science (September 2016)

Christy Goldhawk, Guilherme Bond, Temple Grandin, Ed Pajor: Behaviour of bucking bulls prior to rodeo performances and relation to rodeo and human activities opens in new tab/window, Applied Animal Behaviour Science (August 2016)

Ruth Woiwode, Temple Grandin, Brett Kirch, and John Paterson,Compliance of large feedyards in the northern high plains with the Beef Quality Assurance Feedyard Assessment opens in new tab/window, The Professional Animal Scientist (December 2016) – Open Access

Camille King, Laurie Buffington, Thomas J. Smith, Temple Grandin: The effect of a pressure wrap (ThunderShirt®) on heart rate and behavior in canines diagnosed with anxiety disorder opens in new tab/window, Journal of Veterinary Behavior: Clinical Applications and Research (September-October 2014)

Grandin, Temple: Auditing animal welfare at slaughter plants opens in new tab/window, Meat Science (September 2010)

Contributor

ABD