Enhancing accuracy, inclusion and scientific integrity through sex- and gender-based guidelines

2024年3月14日

Isabel Goldman, MD別

The cover of Cell's new focus issue (Art by Phillip Krzeminski)

Cell’s focus issue on sex and gender in science sheds light on evolving research considerations and gender equity

Precision and accuracy are the hallmarks of good science. Yet when it comes to sex and gender, the language we use in science is open to interpretation. This lack of precision reduces the rigor and integrity of our science. Outmoded essentialist and binary concepts impede our progress.

In 2023, Elsevier, Cell Press and The Lancet incorporated the Sex and Gender Equity in Research (SAGER) guidelines 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く into their information for authors, using these guidelines to develop a special section on reporting sex- and gender-based analyses. Researchers can now find these guidelines in all Cell Press 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く journals, including some of its society partner journals; The Lancet 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く journals; and more than 2,300 Elsevier 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く journals.

Cell’s special issue on sex and gender in science

Today, Cell published a special interdisciplinary issue: Focus on Sex and Gender 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く. The issue is free to read.

The articles expand on and support many of the concepts found in our SGBA guidelines. Among the pieces is an interview 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く with the lead author of the SAGER guidelines, Dr Shirin Heidari 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く. As Dr Heidari describes in her interview, the development of the SAGER guidelines “stemmed from inadequate academic reporting of how sex and gender considerations are integrated into research methodologies, results and interpretation of findings.” The SAGER guidelines “systematically outline how authors can methodologically enhance the presentation of their sex and gender considerations, from the initial research design and methodology selection though to data collection, analysis, and the presentation and discussion of results.”

At Elsevier, Cell Press and The Lancet, we used the SAGER guidelines to develop our own SGBA reporting guidelines, which researchers can now find across all Cell Press 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く journals, including some of its society partner journals; The Lancet 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く journals; and more than 2,300 Elsevier journals.

Cell’s focus issue highlights our commitments to thought leadership in — and enhancing the precision of — sex and gender research. It presents a Perspective on enhancing the rigor and precision of studies involving sex-related variables 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く, and articles on the history 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く and future 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く of sex and gender research. In addition to the interview with Dr Heidari, there is one 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く with Prof Londa Schiebinger 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く — an international leader on the intersection of sex, gender and science.

There are also pieces on gender equity. These include a Commentary from Swiss scientists 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く on how they successfully started to close the classic scissors graph (depicting the institutional gender imbalance that accrues with more senior positions) at their institution.

Finally, the issue features an unprecedented Commentary from 24 transgender (and/or family of trans) scientists 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く on the experiences of sex and gender minorities in STEMM and why addressing systemic barriers that they face will lead not only to a just, equitable and diverse STEMM academy but also to more rigorous science.

Guidelines on reporting sex- and gender-based analyses

In the span of a year, our journals’ information for authors went from containing little information on sex and gender to presenting unified state-of-the-art guidelines across thousands of journals. These guidelines increase the equity and impact of the science we publish. As we created them, three principles guided us:

Accuracy

Inclusion and

Scientific integrity

How our SGBA guidelines lead to equitable and impactful science

Accuracy

We want to maximize the precision and accuracy around the language of sex and gender in our science. This in turn will increase its rigor and reproducibility. As scientists, we strive for accuracy and precision, yet when it comes to the science of sex and gender, we often labor under the assumption that what one person means by the terms “sex” and “gender” is what another person means, when that is not always the case. It is generally accepted that scientific knowledge evolves over time, and the science of sex and gender is no different.

“As scientists, we strive for accuracy and precision, yet when it comes to the science of sex and gender, we often labor under the assumption that what one person means by the terms ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ is what another person means, when that is not always the case. It is generally accepted that scientific knowledge evolves over time, and the science of sex and gender is no different.”

IG

Isabel Goldman, MD

Cell Press, Elsevier, Inclusion & Diversity Officer at Cell Press | Leading Edge Editor at Cell

Our guidelines provide definitional recommendations for using the terms “sex” and “gender” in research. Such discussions, particularly those that steer us away from outmoded binary notions of sex and gender, are much needed. As Dr Beans Velocci describes in their Benchmark article “The History of Sex Research: Is "Sex" a Useful Category? 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く”, the multiplicity of sex definitions throughout the history of sex-based research has caused it to mean “just about everything, and therefore also nearly nothing.”

The historic malleability of the term “sex” in research has allowed it to encompass whatever researchers need it to mean within a certain research context. As such, it often functions as a simplified, binary variable that captures multiple, distinct traits and characteristics, many of which researchers don’t actually assess. We attribute biological causation to the variable rather than any actual trait, characteristic or property. In their Perspective “Sex contextualism in laboratory research: Enhancing rigor and precision in the study of sex-related variables 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く,” Pape et al. document how the first step towards better understanding sex-related variation in health and disease is to acknowledge that “sex is not in and of itself a causal mechanism.” That is, sex per se is not a biological variable. Instead, it is a “classification system” with categories that encompass an array of varying and overlapping traits. Or as the National Institutes of Health’s Office of Research on Women’s Health now defines it 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く: “Sex is a multidimensional biological construct based on anatomy, physiology, genetics, and hormones.” Pape et al. urge researchers to move “beyond sex as a system of classification” toward “working with concrete and measurable sex-related variables.” So, too, do our guidelines ask authors to consider how they operationalize the terms “sex” and “gender” and describe what they are measuring or assessing and what they are not. Have you assessed chromosomes? Hormone levels? Are you actually witnessing a gendered effect? This deconstruction of “sex” within a given research context is necessary for precision.

By delineating “sex” as in sex-related characteristics, only some of which might be relevant within a given context, from “sex” as a categorization, our guidelines avoid the conflation of disparate concepts. This conflation has, in recent years, caused significant harm. This is particularly true for transgender, intersex and gender diverse people whose “existence,” as Aghi et al. describe in their Commentary “Rigorous Science Demands Support of Transgender Scientists 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く,” belies “imprecise and simplistic notions of sex and gender,” chief of which are that both are binary and immutable. In the article “The Future of Sex and Gender in Research 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く,” multiple authors comment on these fallacies. When it comes to “brain sex,” Dr Jessica Tollkuhn notes that it “is a flexible state defined by fluctuating sex hormones, rather than immutable sex chromosomes.” Dr Xiaohong Xu describes how when viewing sex-based differences, “misconceptions arise due to the perception that these sex differences are binary” rather than “variations between two overlapping curves.” And Dr Elle Lett summarizes the effect that binary thinking has had: “Science’s rigid commitment to binary sex and gender quashes creativity and limits progress.”

In keeping with its goal to make our science more accurate, our guidelines steer authors towards precise terms like “sex assigned at birth” and away from vague and ambiguous ones, like “biological sex.” Finally, the guidelines suggest how authors can ask about sex and gender during their next research cycle — emphasizing a two-step process that centers gender identity first and sex assigned at birth second and only if relevant.

Inclusion

We want our science to reflect the full diversity of the human experience. As we make our science more inclusive, we necessarily make it more precise and accurate. Researchers have historically excluded trans, intersex and gender-diverse voices from conversations about sex and gender. Our guidelines incorporate their perspectives and lived experience as invaluable resources, and Cell’s focus issue centers them. “There is no contradiction between rigorous science and the existence of trans people,” write Aghi et al 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く., and trans people welcome research on sex and gender “if and only if these research programs are rigorous enough to be ethical and their social applications are accountable to those impacted by their methods, findings, and interpretations.” If we were to move beyond binary constraints, Dr Lett envisions 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く how “people with differences in sex development [intersex] wouldn’t be pathologized but would be seen as honoring the diversity of which human biology is capable.”

Inclusion does not, however, necessarily imply a lack of exclusion. As Aghi et al. outline in their Cell Commentary 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く, certain sociopolitical groups, particularly in the United States but also in the United Kingdom, Europe and elsewhere, have increasingly co-opted, misappropriated and misused the science and language of sex and gender to create a thin scientific veneer to cover exclusionary agendas. These agendas not only impact people’s rights, but for some, threaten their existence 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く leading to, for example, calls that “for the good of society … transgenderism must be eradicated from public life entirely 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く.” The use of science to bolster such agendas against some of the most marginalized people — a tactic for which we have ample historical precedence — lays the groundwork and creates a framework to move up the marginalization ladder, allowing exclusionary groups to progressively curtail more and more people’s rights with pseudoscientific rationales. As biomedical publishers we, in part, function as stewards of the literature. It is therefore our duty and responsibility to advocate against such misuse of science. One of the best ways we can do that is to maximize our science’s precision, accuracy and inclusivity. By including so many voices and perspectives historically excluded from sex and gender discussions, Cell’s focus issue on sex and gender strives to do that.

Scientific integrity

“Overlooking the impact of sex and gender,” writes Dr Heidari, “perpetuates gender disparities in healthcare.” If our science doesn’t fully and precisely consider dimensions of sex and gender, it runs the risk of spurious conclusions, which have the capacity down the line to cause patient harm. As Dr Schiebinger asserts in her interview with Cell 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く: “Reflexively generalizing from studies in men or any majoritized group to inform women’s, or any minoritized group’s, healthcare can lead to harm.” This is true when we’re studying men or males and attempting to generalize to women or females, or whether we’re studying cisgender people and intending to extrapolate to transgender people. Accurately and completely describing the limitations of the generalizability of one’s research is an important scientific process with potential significant health impacts. It is also true, as Dr Schiebinger notes, that “‘gender’ often unconsciously translates to women.” And it is “a common misconception,” Dr. Heidari finds, "that integrating sex and gender perspectives into research exclusively benefits women.” Robust sex and gender analysis benefits all genders.

With the advent of sex- and gender-based analyses comes the risk that we could inadvertently swing too far the other way. The danger of imprecise sex and gender analysis is, as Pape et al. chronicle 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く, the reporting of unsupported sex-based differences through failure to distinguish between sex categorization and specific biologically-relevant sex-related variables. Dr Schiebinger describes how “sex or gender analysis is not one thing you do, such as including equal numbers of male and female rats in an experiment.” Rather, such “analysis must be considered in each step of the research process from identifying the problem (setting research priorities) to designing the research, collecting data, analyzing results, and reporting.” It’s not just a matter of considering sex and gender. How one does so, at each stage of the research cycle, is critically important.

Traditionally, sex and gender research has been divided into two camps: the life sciences and social sciences. This issue of Cell, recognizing the importance of cross-disciplinary inclusion when it comes to discussing sex and gender in science, mixes the social and life sciences. “Advancing the science of gender and sex,” writes Dr Rebecca Jordan-Young 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く, “requires robust interdisciplinary collaboration, particularly with gender and sexuality scholars outside of biological disciplines.” This advancement will require a paradigm shift. “Sex and gender analysis,” Dr Schiebinger tells us, “was developed in the humanities and social sciences and has, for the most part, not made its way across disciplinary divides to other parts of the university.” This sort of research, write Pape et al., is “ideally informed by the social sciences and gender studies literature, particularly that which considers the social dimensions of sex-related variation in health and biological outcomes.” Dr. Jordan-Young cautions us that true, robust collaboration will require addressing the longstanding, “uneven institutional power and epistemic authority among disciplines whereby biosciences are afforded primacy over other disciplines.”

Cell’s focus issue is an example of this cross-disciplinary approach to understanding sex and gender. It is the ability of social and life scientists “to ask different questions and use different methods,” Dr Velocci argues, “that strengthens cross-disciplinary collaboration.” When it comes to sex, both life and social scientists know “equally important but separate things about it.” And “[c]ollectively … we know quite a lot.” Combining these two knowledge bases and learning from each other will result in more impactful sex and gender research.

The SGBA guidelines in action

In May 2023, Cell published an article 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く on best practices for testing genetic models of sex differences in large populations. Lead author Dr Ekaterina Khramtsova 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く describes her experience with the SGBA reporting guidelines and how they impacted her work:

The guidelines provided by Cell Press on reporting sex- and gender-based analyses (SGBA) have been instrumental in shaping and enhancing our article titled "Quality Control and Analytic Best Practices for Testing Genetic Models of Sex Differences in Large Populations." They have played a crucial role in ensuring that we adhere to best practices and accurately address the complexities of sex and gender in genetic analyses. We recognize the importance of integrating sex- and gender-based analyses in our research, as it is crucial for understanding the mechanisms driving sex-based differences in complex traits. By following the clear definitions of "sex" and "gender" outlined in the guidelines, we promote inclusivity and precision in reporting sex-related data, avoiding conflation of terms and ensuring accuracy. Moreover, we align our work with the guidelines' objective of achieving diversity, equity, and inclusion in research, as we highlight that sex-aware analyses contribute to the goals of precision medicine and health equity for all.

Acknowledging the evolving nature of the field and potential research limitations related to sex and gender, we take into account the guidelines’ recommendation to discuss such limitations, ensuring that our article provides a well-informed and accurate contribution to the understanding of sex-dependent genetic effects.

Ekaterina Khramtsova, PhD

Equality in STEMM

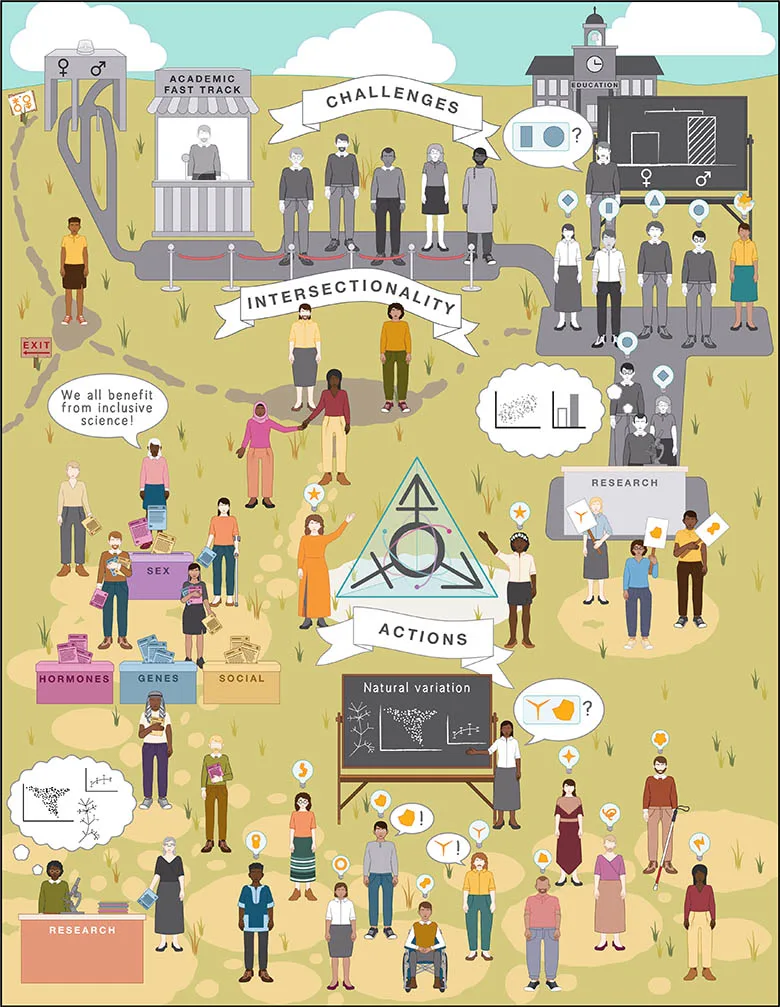

Robust sex and gender analysis will lead to greater gender equality. And inclusion of traditionally excluded voices and disciplines to the conversation is an important equity and rigor-enhancing step. Yet we must also acknowledge the pervasive nature of gender inequality in STEMM fields. It’s not just the “what” or “how” of our science, but also the “who.” Joyce et al. describe 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く how this inequality manifests as a “progressive decline in the representation of women at successive stages of the scientific and academic career trajectory.” And we visualize that with the infamous scissors graph.

The scissors graph

In their Commentary, Joyce et al discuss drivers of the scissors effect and strategies to stem the flow of talented women out of STEMM.

To bring equality to STEMM, whether for women, sex and gender minorities or marginalized groups in general, requires a culture shift. Joyce et al. note “the inherently slow pace of cultural transformation.” It is a change that must be “profound and must be far-reaching.” The process to get there is one in which “complacency has no place,” for “it demands consistent and dedicated effort to achieve lasting change.” Aghi et al. remind us that “When we build institutions and systems to support all who contribute, we move to rectify scientific inequity and injustice.” By “include[ing] people from all walks of life,” they write, “we enrich STEMM with unique perspectives that reveal new ways to explore nature’s creativity.”

Inclusive Science Benefits All. (Image by Julie Sung based on schematics from Simón(e) Sun)

Conclusion

Whether we seek to improve the reporting of sex and gender in research, heal the damage wrought by the historic exclusion of certain voices from sex and gender conversations or close the open scissors and end the progressive gender disparity that plagues STEMM, our struggles are common. Working towards equality in STEMM requires relentless advocacy, crafting and implementing equitable solutions, navigating institutional and personal apathy, overcoming epistemic injustice (“the idea that one can be discriminated against as a knower or wielder of knowledge based on identity, and attendant differences in ‘ways of knowing’ 新しいタブ/ウィンドウで開く”), urging the majoritized to confront, rather than dismiss, their uncomfortable feelings and, importantly, institutions that provide resources and support this work.

The SGBA guidelines of Elsevier, Cell Press and The Lancet, and Cell’s focus issue, are examples of how combining interdisciplinary thought leadership and advocacy can inspire potentially sustained and profound change.

貢献者

IGM

Isabel Goldman, MD

Inclusion & Diversity Officer at Cell Press | Leading Edge Editor at Cell

Cell Press, Elsevier

Isabel Goldman, MDの続きを読む